Adrienne, off to Terabithia (1918)

After writing about childhood and atheism the other day, I had a feeling it’s finally time for my Adrienne post. Specifically, Adrienne Von Speyr, the only subject I have in my blog roll. This is a very long and meandering post, as I am knitting together the threads of several different, proto-posts that never went anywhere.

I.

I read Bridge to Terabithia when I was a boy. I have not read it since, but it made an impression, as I could remember the story reasonably well years later. After I saw the film adaptation in 2007, fragments started coming back to me, about names that could go either way, and the feel of a sweater button pressed into your face. I would think about the book from time to time, and why I still remember it when so many other books from my youth have gone away.

In hindsight, I think it must have been the alien abduction quality of the friendship at the core of the story. Jesse Aarons, an artistic 11 year old boy, becomes best friends with … a girl, his classmate Leslie Burke. Maybe things have changed, but based on my school experiences, I think on a subconscious level this required more suspension of disbelief by my eleven year old self than E.T. The Extraterrestrial.

It is not a casual friendship. She is the shy Jesse’s only friend, and they spend just about all their free time together. She is the more mature and developed personality. And an atheist of all things too, in contrast to Jesse’s church going family. I do not recall any sexual tension in the book, and Jesse’s budding romantic affections seem entirely channeled into a crush on his pretty art teacher, Miss Edmunds. But the friendship with Leslie, however brief, has a profound effect on Jesse. She teaches him how to love, and to live life despite its hardships.

The book’s author, Katherine Paterson, was the daughter of Christian missionaries, and had intended to become a missionary herself before she turned to writing.In an interview she acknowledged that we live in a post-Christian culture, but that we write what we are, and so she writes stories that convey messages of grace and hope for the reading public that we have, and not the one that perhaps we would prefer.

Looking back, I feel a certain jealousy for Jesse, because I never had a Leslie Burke in my life at that age. And once a boy becomes a man, it is difficult to have a strong, platonic friendship with a woman. J.R.R. Tolkien put it very well in a letter to his son that’s worth reading if you can find it (#43). An excerpt:

This ‘friendship’ has often been tried: one side or the other nearly always fails. Later in life, when sex cools down, it may be possible. It may happen between saints. To ordinary folk it can only rarely occur: two minds that have really a primarily mental and spiritual affinity may be accident reside in a male and a female body, and yet may desire and achieve a ‘friendship’ quite independent of sex. But no one can count on it. The other partner will let him (or her) down, almost certainly, by ‘falling in love’. But a young man does not really (as a rule) want ‘friendship’, even if he says he does.”

Terabithia is Eden before the fall, when love was undimmed by lust or possession. There is no real sin in Terabithia, but Leslie suffers a fall at the end, and it means her death. Jesse was on the precipice of puberty, and Leslie was alone at the end because Jesse chose to go on an outing with his crush. Is “growing up” a kind of death? And death a return to childhood?

II.

Contemporary imagination is haunted by women like Leslie Burke, impressive women who lived young, and died hard. A few examples: Bernadette Soubirous (St. Bernadette), Marie-Francoise Therese Martin (St. Therese of Lisieux), and Elisabeth Catez (St. Elizabeth of the Trinity). The Church calls them Saints, but for the Modern World they might as well be ghosts, because it does not believe in them.

(Bernadette, Marie-Francois, and Elisabeth, before the convent life)

While there were a fair number of these young female saints in the Church of Antiquity (pre-500 A.D.) and Middle Ages (500 to 1500 A.D.), very little is known about most of them. The more famous female saints tended to be the longer lived scholars or founders and reformers of religious orders (Clare of Assisi, Hildegard, Catherine of Siena, Scholastica, and Teresa of Avila).

One exception is Joan of Arc, who died at 19 in 1431. And in a way, I see her as almost a bridge from the young visionaries of the past to those of the present age. And we arguably need a bridge, because the world before Joan seems to have been more accepting of mystic possibilities.

The mystery of Joan has been on my mind the last few years. Why would God care about a dynastic conflict between two Catholic countries? There was no great religious question tied up in the 100 Years War. And her death did not bring a swift end to the war or reconciliation between England and France. The war continued for another twenty years, and England and France remained bitter rivals until the 20th century.

From the French film, The Trial of Joan of Arc.

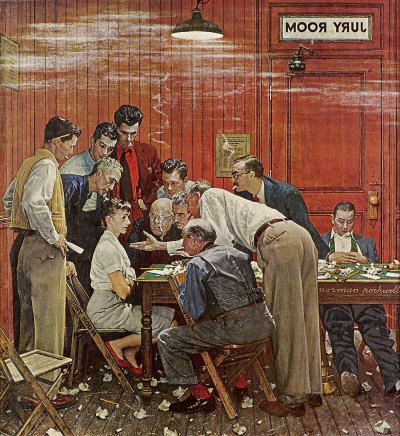

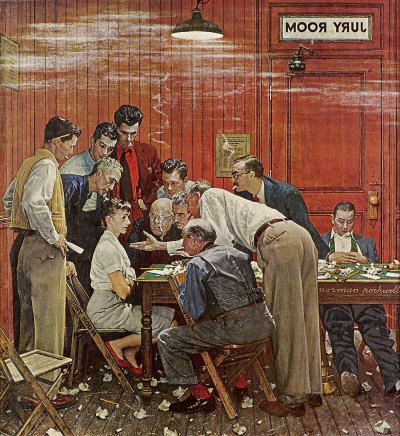

While I like the poster above, I think an even better portrayal of her situation is Norman Rockwell’s painting, “The Jury.” I post it below to show how a contemporary image may better explain the question of Joan.

The Jury, from Saturday Evening Post, February 14, 1959

The painting seems to illustrate her dilemma very well. She was pressed in on every side, with her accusers making appeals to reason, as well as appeals to authority. Today’s Christian must face the same appeals from the modern world. The reddish room and smoky air call to mind what she was threatened with in this life and the next if she did not recant. And is that the Devil on her left shoulder, all in red?

While Joan was charged with heresy, she was not executed for her visions. Technically, she was executed because she was a repeat offender against the Biblical clothing rule prohibiting cross-dressing, the only thing they could actually prove. Leslie the tomboy would smile at that. But the major reason she was not spared was that she would not give in to the demands of her accusers. They wanted her to renounce her visions of the saints. If she had, she would have been allowed to live. So, she was put to death for keeping faith with what Modern World thinks of as ghosts. Burnt to ashes, and cast in the river. Leslie’s sacrifice was the reverse, drowned and then cremated.

And which saints were they? None other than St. Michael the Archangel, and St. Margaret and St. Catherine, two virgin martyrs who died at 15 and 18, respectively. That’s our Church in the world’s view: Girl ghosts and invisible angels all the way down. All the way back to the Blessed Mother and the angel no one else ever saw.

Blessed is he who is not scandalized by Me.

Joan’s conviction was set aside by the Church after a retrial a few decades later. Those who die for their faith are deemed to be saints, but she was not canonized until the 20th century. But again, what was Joan’s mission? She said it was to “Save France,” and many have puzzled over the years as to why God would care about this war. Some have theorized that by saving France, Joan preserved the Church through the struggles of the Reformation. If England had conquered France, it might have become a Protestant nation later on. Perhaps there would have been no Counter-Reformation, and none of the great French saints and theologians of the past few centuries would have come to be.

Let me suggest a set of additional or alternative missions for Joan: Perhaps Joan’s message to the world was her great “No” to secular authority, which was really a disguised “Yes” to God. Joan was trying to teach the Church how to say no to the comfortable position of political power it enjoyed at the time. The English influenced branch of the Church did not learn this lesson and killed her. Exactly one hundred years later the same branch was unable to say no to Henry the VIII (at the Convocation of 1531), and then it died.

On a personal level, she was the model for the mystics and visionaries of the Modern World, an age in which God has been declared to be dead, and even the Church rightly looks with caution on those who claim to talk to the saints. Perhaps Joan of Arc had to die so that the Church would always pause and take notice of the Maid of Lourdes, the Little Flower or a Sister Faustina before it made a decision. Joan gave them room to breathe and be believed. Joan also gave our girl ghosts a model for courage, a pattern to follow. And hope, that even if they were killed, providence would take care of them in the end. If Joan could do this, so can I.

III.

When Hans Urs von Balthasar died in 1988, his funeral eulogy was given by his friend and mentor, Cardinal De Lubac. The Cardinal, in his opening remarks, quoted theologian Ludwig Kaufman’s observation about the missing man of the Second Vatican Council:

… It is disconcerting that from the first summons of the Council by John XXIII, it did not seem to have occurred to anyone to invite Hans Urs von Balthasar to contribute to its preparatory work. Disconcerting, and – not to put a tooth in it- humiliating, but a fact that must by humbly accepted. Perhaps, al in all, it was better that he should be allowed to devote himself completely to his task, to the continuation of a work so immense in size and depth that the contemporary Church has seen nothing comparable.

Von Balthasar died two days before he was to be made a Cardinal . The theologian’s life long case of shyness had finally turned terminal. He had refused the honor before, but finally acceded out of obedience to his friend Pope John Paul II.

Who was Hans Urs Von Balthasar? Cardinal De Lubac also referred to in his eulogy as the man “most cultivated of his time.”

An eternal child, and apparently his favorite picture of himself

He said he never planned on being a priest as a young man. His first love was music. But on a retreat in the Black Forest, the call came to him like lightning while standing under a tree. He joined the Society of Jesus in 1929 and was ordained in 1936. He went on to become one of the most prolific Catholic theologians of the 20th century, and received many awards. He was appointed to the Church’s International Theological Commission in 1969, and founded the theological journal Communio with his friend and future Pope, Benedict XVI, in 1972.

So why wasn’t he at Vatican II? Well, he left the Society of Jesus in 1950, and was without a job for six years. He had effectively given up what was likely to have been a very secure, comfortable and prestigious career in academia. And all over a woman.

Blessed is he who is not scandalized by Me.

IV.

Adrienne von Speyr was born in 1902 in Basel, Switzerland into a Protestant family. Her father was a successful doctor, and she had three siblings. Her public life was very ordinary in many respects. Interesting, honorable, and marked by the kinds of hardship and setbacks that many of us face, but ordinary.

Her father died of a sudden illness when she sixteen, and the family had to adjust to a much reduced standard of living. Worn down by school and taking care of their home, she was diagnosed with tuberculosis in both lungs in 1918. She spent the next three years in a sanitarium in the Swiss Alps, and initially, was not expected to live. Her mother visited her one time in those three years. If you ever read Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, Adrienne lived that book in a way. She met a number of interesting people, and picked up Russian from the many Russian refugees in Switzerland.

After her recovery she decided to go to medical school, contrary to her mother’s wishes. She persevered, and worked her way through medical school and was admitted to the profession. She was not supported by her family, and tutored many students to pay her way. She married a widower with two young sons in 1927, and started her own medical practice in 1931. She was a very busy, respectable physician, and much commended for her care of the poor. Unfortunately, her husband, who she had come to love very much, died in an accident in 1934. She married again in 1936. She never had any children of her own.

All this time she was searching for something, dissatisfied with her spiritual life. She had a significant interest in Catholicism, but could never find a bridge in her largely Protestant circle of friends and associates. She finally met Father Von Balthasar in 1940. She formally converted later that year under his guidance. This conversion was something of a shock to those around her, and resulted in alienation from her family and some friends. Father Von Balthasar became a good friend of Adrienne’s family, and they provided a room for him in their own home during his years in the wilderness.

Adrienne stayed very busy with her practice throughout the 1940s, but her health did not hold out. She had a severe heart attack, and then developed diabetes. By the mid-1950s, she was effectively housebound, and had to give up her medical practice. Her remaining years were marked by significant suffering. She was functionally blind by 1964, and died of colon cancer in 1967.

While her health had been declining, Adrienne had taken up the pen to write books of scriptural commentary and spiritual reflections, despite no formal training in theology or philosophy. Her first book, Handmaid of the Lord, was published in 1948 by a company, Johannes Verlag, that Von Balthasar had founded. Additional works about scripture, prayer or the sacraments were published every few years until her death. Adrienne’s published works garnered no great attention and were not widely available in English during her life. T.S. Elliott did provide a favorable jacket blurb for her Gospel of John commentary, which was published in 1949:

“Adrienne Von Speyr’s book does not lend itself to any classification I can think of…. there is nothing to do but submit oneself to it; if the reader emerges without having been crushed by it, he will find himself strengthened and exhilarated by a new sense of Christian sensibility.”

V.

The thing about giving your consent to God is that He will pay you the compliment of accepting and running away with it for the rest of your life. You will find yourself dragged along, no matter how tired you get. You might find yourself, like Adrienne, writing pages and pages of a letter, and mailing it off to a friend, not realizing that the ink had run out because you were blind.

Blindness to hope can also lead a soul to a very dark place. You might find yourself, like Adrienne in her younger days, staring into the beckoning depths of Rhine River from a railway bridge at the darkest moments of your life.

Despite all this, she was described by Von Balthasar as a lively, cheerful and fearless woman:

She was marked by humour and enterprise. She was like the boy in the fairy tale who sets off to experience fear. At her mother’s instigation she had to leave high school but secretly studied Greek at night by the light of a candle, so she could keep up with the others. In Leysin she learned Russian. After her transfer to the high school in Basel, she quickly learned German and at the same time took a crash course in English to catch up with the rest of the class. As I said, she paid for her medical studies by tutoring. Then there is her courageous readiness to stand up for justice. When a teacher struck a boy in the face with a ruler, she rushed forward, turned the teacher to the face the class, and shouted: “Do you want to see a coward? Here’s one!”

Blessed is he who is not scandalized by Me.

After she died, Father Von Balthasar gradually revealed the mystery of his own career path for the prior twenty years, and the mystery of Adrienne’s life. What was learned was a great surprise to her family, friends and the larger world.

Adrienne wrote a partial biography of her life through her first 24 years, in which she revealed she had visions of the saints since she was a child. She had experienced significant emotional turmoil, and considered suicide twice, once over her family relationship, and the second time after the death of her first husband.

She had suffered stigmata on a regular basis after her conversion, and she had dictated about sixty works of scriptural commentary and spiritual reflection to Father Von Balthasar between 1945 and 1953. He had published only a small portion of her output during her life, and the ones that would be the least controversial.

Her mystical experiences had increased tremendously after her conversion in 1940, and Von Balthasar had attempted to have the Society of Jesus take over the mission of evaluating and caring for her mission. For reasons too complicated for me to explain, they refused, and he was given a choice of either staying in the Society or leaving to be her personal spiritual director. He felt that Adrienne had been called to a special mission by God, and left the SJ in 1950 to be her confessor and publisher for the next seventeen years.

After her books became better known, some in the Church were impressed enough that a scholarly conference was held in her honor in Rome in 1985, at which Pope John Paul II spoke approvingly of her work. But overall, there was no groundswell of acceptance for her work between her death and Balthasar’s in 1988. However, he maintained to the end the importance of her influence on his own theological output in various statements:

“[O]n the whole, I received far more from her, theologically, than she from me.”

“Today, after her death, her work appears far more important than mine.”

He wrote his last book about her, Our Task: A Report and Plan, with one purpose: “… to prevent any attempt being made after my death to separate my work from that of Adrienne Von Speyr.”

While Von Balthasar received great praise in the last few decades of his life, and which has endured to the present day, he is not without his critics. His theology has offended and been subject to criticism from various points on the x, y, and z axis of the theological spectrum. I am not a scholar or theologian, so I have no opinion worth mentioning on these issues.

Nor has his endorsement of Adrienne been widely accepted, at least publicly. I once read a 400+ page review of his theology that included eighteen different chapter commentaries by theologians of various denominations. In the introduction, the editor warned that one must come to terms with Von Balthasar’s insistence that his theology was derived from hers. The vast majority of the contributors proceeded to ignore that guidance, and the few that mentioned her gave her only passing references.

There have been three books written about her, a number of Ph.D dissertations, and a large number of scholarly articles in various journals. Yet, for me at least, the silence speaks volumes. With a handful of exceptions, you will not find any Cardinals, Bishops or famous theologians opining favorably about her work. Possibly its polite embarrassment. A number have openly said they have no idea what he saw in her work. A more benign view is that the Church is, like Mary did once, keeping “all these things within her heart,” and watching to see whether any fruit ripens.

There are certainly very public negative criticisms of her work and her relationship with Von Balthasar, and they are easy to find. And in this age of scandal, it should not be a surprise that they are made against a man and woman who spend such a large quantity of time in each other’s company, even when there is no evidence of any impropriety.

Blessed is he who is not scandalized by Me.

VI.

One of the benefits of being a sinner, layperson, mediocre Catholic and anonymous blogger is that you have no great reputation that needs regular care and maintenance. So I am free to offer my non-scholarly and uninformed endorsement. Adrienne has made a big difference in bringing me back to the Church, and if you are looking for something, perhaps she will help you too.

If you are curious, I would recommend The Passion from Within as a good starting point. Adrienne was relentlessly Christocentric, and you may find yourself developing a closer connection with the Lord after reading it.

You might even think about going to confession again (if you have not been), and even on a regular basis (not yearly, slacker!). Her book on this topic, Confession, is very insightful.

The magnum opus is the four volume commentary on the Gospel of John. This is a line by line exegesis, and her longest work. All the themes of her bibliography are touched on in way one or another there. Fair warning, it can be a heavy read, and you will want to take breaks regularly.

Lastly, I will mention the Book of All Saints. This book is about the contemplation and prayer life of the saints, and Von Balthasar called it a “great gift to the Church.” I think it is the book that will ultimately make or break many people’s view of Adrienne. I will quote from the section about Joan of Arc, as she was at the end:

She is soft and gentle and bears what is given to her to bear: before, she had borne things for the Christian king; now she understands that her mission is expanding and that she has to bear things for all believers. The end is not “heroic”, but completely pure, without blemish, as simple as only a childlike faith can be, and perfectly trusting.

Blessed is he who is not scandalized by Me.

A veil is always drawn over a confessor and the sinner, and a spiritual director and his charge. While there is some portion of her work that remains to be published, a large share of Adrienne’s mission will have to remain a mystery to us.

And there will always be doubt about its authenticity. If you listen, you can almost hear the sigh of disappointment from many of the learned and wise in the Church:

“Hans, Hans, why did you have to run off to Terabithia with that girl? You were meant to be the great navigator for the Church between the bastions of the past and the shoals of modernity. And yet, like Odysseus, you seem to have tied yourself to the mast to listen to the siren call of some mystic. Why, why?”

And if you listen closely, you might hear the answer, however partial and incomplete:

“She was my friend.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.